Comets are time capsules containing original material left over from the epoch when the Sun and its planets formed. But before scientists planned the Rosetta mission only a handful of spacecraft had ever observed one up close for a short time only – let alone pushed space science to its limits by trying to follow a comet and even land on one…

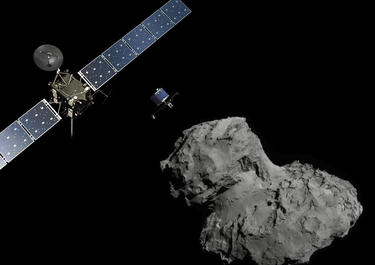

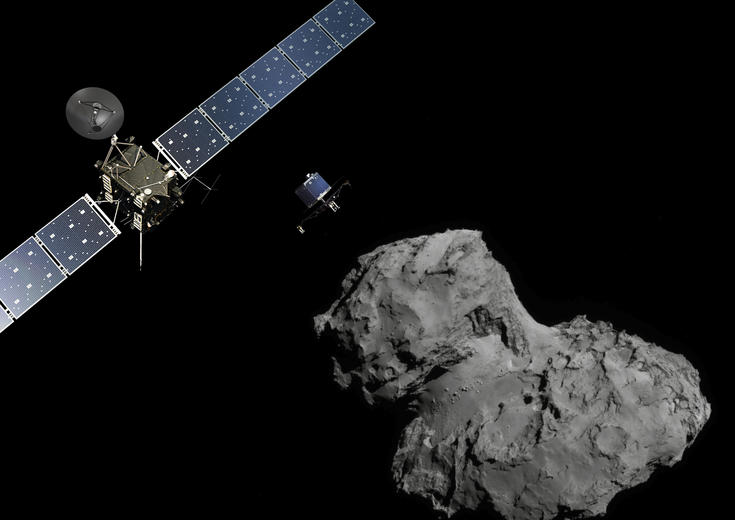

20 years ago on 2 March 2004 the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission lifted off on an Ariane 5 from French Guiana to make a 7.9 billion kilometre trip to rendezvous with comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko (67P for short) and then despatch its tiny lander Philae onto the surface.

But 67P was not the original target for the Rosetta mission – it was actually due to head for comet 46P/Wirtanen in 2003, however after a problem with an Ariane 5, the launcher was grounded until the fault was found, and Ariane 5 was ready for the next launch. This meant the scientists had to hunt for a new target with a similar orbit as they only had one chance to catch that comet.

During its 10 year journey, the Airbus-built Rosetta performed a series of orbital manoeuvres using the gravitational pull of the Earth and Mars to act as a sling shot to pick up acceleration and reach the 55,000 km/h (over 15km per second!) it needed to catch up with 67P. Travelling at this speed and trying to rendezvous with the comet only 4 km wide was described as like a fly trying to land on a speeding bullet. Rosetta actually reached 123,000 km/h when shadowing the comet at the closest point to the Sun.

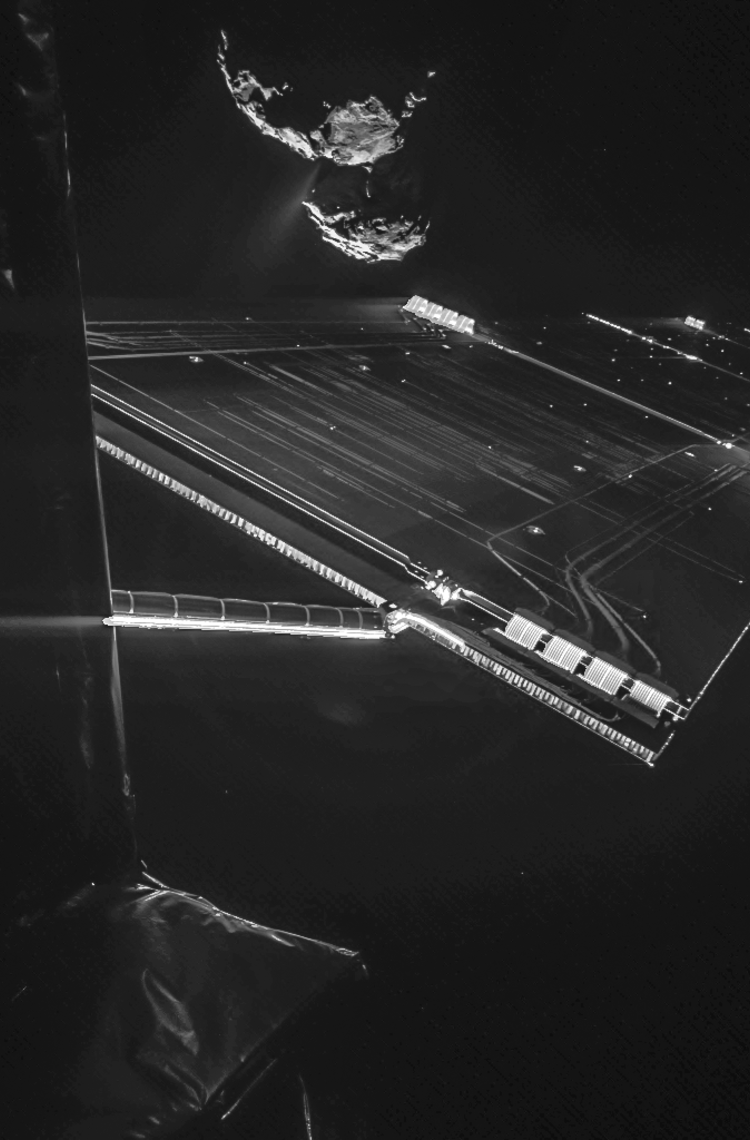

In July 2011, Rosetta was put into hibernation for its cold and lonely journey chasing 67P. It was kept alive by heating with the equivalent of just six lightbulbs to stop freezing its fuel. Thankfully in January 2014 the spacecraft was successfully woken up by 4 pre-programmed internal alarm clocks and started its tricky final approach to 67P. On 6 August 2014 its thrusters put the spacecraft into an orbit just 100km above the comet and matching its speed through space. Now Rosetta started its work, by measuring all the parameters of the comet, and by scanning and mapping the surface of this unknown body, to find a place to land on it.

Everyone remembers the tiny lander Philae bouncing down onto the surface of the comet – but this was only one of Rosetta’s achievements and discoveries. Equipped with 11 instruments Rosetta managed to take amazing measurements of the comet when it was inactive and then studied it as it approached the Sun and became active. And crucially also saw what happened when it flew away from our star and calmed down again.

On its journey Rosetta had to survive the searing heat of the Sun from the distance of Venus, as well as temperatures dipping down to minus 270°C in deep space from the distance of Jupiter, all the while making sure its fuel did not freeze.

As Gunther Lautenschlaeger, who was Airbus’ Rosetta project manager at the time said: “Reaching out behind the horizon, where nobody had been before, was incredibly challenging, we had to develop new concepts for the spacecraft so it could operate and survive autonomously. What we achieved has paved the way for many modern Airbus spacecraft.”

One example is the huge solar arrays developed to keep Rosetta alive at its furthest point where there is only 4% of sunlight compared to Earth’s orbit. This revolutionary technology enabled the arrays to be developed for JUICE, launched in 2023, which is successfully heading for Jupiter and its icy moons.

The lander Philae achieved a world first of landing on a comet – and it successfully carried out the majority of its mission sending scientific data up to Rosetta for onwards transmission to Earth. Its final resting place was sadly too shady to keep its batteries charged and so after 55 hours it went into hibernation.

Incredibly more than six months after it went silent in its shadowy landing spot, Philae came back to life on 14 June 2015 and pinged Rosetta. And started to send back more of its unique, invaluable data. It was early September 2016, towards the end of the momentous mission, before the first picture revealed where Philae had ended up, wedged in a dark crack that was christened Abydos.

And finally on 30 September Rosetta was instructed to make a controlled descent onto the comet’s surface – but unlike other exploration missions which are high velocity impacts, Rosetta’s touchdown was made at a sedate walking pace of 2 km/h.

Everyone will always remember the comet landing of Philae, but that would have been impossible without the amazing Rosetta spacecraft. Not only did it manage to rendezvous with the comet, but also successfully orbited it for more than two years, at altitudes from 100km right down to 2 km. With signals taking up to 40 minutes to reach the spacecraft from Earth. Rosetta’s autonomous navigation systems had to work perfectly to provide all 11 scientific instruments with a perfect view of the comet. Their journey together lasted from deep space well beyond the asteroid belt, right down to the closest approach to the Sun and out again, continuously scanning the comet, generating huge data volumes, and also of course, taking hundreds of incredible photos. A real mission to remember.

Facts & figures:

Launch: 2 March 2004

1st Earth gravity assist: 4 March 2005

Mars gravity assist: 25 February 2007

2nd Earth gravity assist: 13 November 2007

Asteroid Steins flyby: 5 September 2008

3rd Earth gravity assist: 13 November 2009

Asteroid Lutetia flyby: 10 July 2010

Enter deep space hibernation: 8 June 2011

Exit deep space hibernation: 20 January 2014

Comet rendezvous manoeuvres: May - August 2014

Arrival at comet: 6 August 2014

Philae lander delivery: 12 November 2014

Closest approach to Sun: 13 August 2015

Mission end: 30 September 2016

Airbus-built Rosetta was the first spacecraft to ever orbit a comet, and its lander Philae, the first to land on a comet.

In total, Rosetta travelled nearly 8 billion kilometres.

The Rosetta spacecraft did the mission with 11 Instruments on-board.

Rosetta needed 10 years to get up to the same speed as the comet.

Rosetta was able to follow the comet at a speed from 55,000 (at rendezvous) up to 123,000 km/h (at Sun closest point).

Mass of the orbiter was less than 3 tons, otherwise not possible to reach the comet - though there were 1,670 kg of fuel on board. The science payload weight 165 kg and the Lander (Philae) 100 kg.

Dimensions: Orbiter: 2.8 × 2.1 × 2.0 m with two 14 metre long solar panels

High performance Solar Arrays (68 m2) in both distances.

During its hibernation, which lasted over 900 days before approaching the comet, Rosetta was so far away from the Sun that the solar arrays could only get 400 watts of energy from the Sun, the equivalent of just six lightbulbs!

Learn more on Space topics here.

Your media contacts

Contact us

Ralph Heinrich

AIRBUS | Defence and Space

Jeremy Close

AIRBUS | Defence and Space

Guilhem Boltz

AIRBUS | Defence and Space

Francisco Lechón

External Communications - Airbus Space Systems, Spain