Article: Heather Couthaud

Media: Airbus Helicopters

Read more about sound innovation and hybridisation in Rotor Magazine N°117

As air taxis and package-delivery drones come to the brink of providing air mobility options for cities, sound reduction for aircraft is increasingly stepping into the spotlight. Can new research really impact helicopters’ sound levels? Below, a look at the ways Airbus is trying to lower the volume of its rotorcraft.

Where does the sound come from?

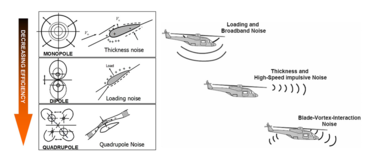

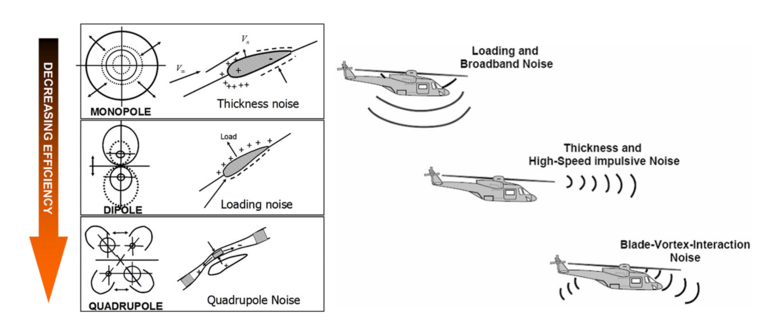

The main source of sound from a helicopter comes from its rotor blades. Blades produce several types of sound. Some are due to air displacement (thickness noise); others (loading noise) are from forces acting on the air that flows around the blade—these are caused by lift and drag, for example. Still other sounds come from aerodynamic shocks on the blade surface, or interactions with turbulent inflows of air.

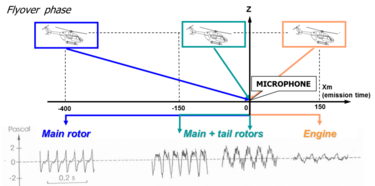

The engine and gear box can generate sound, too, but this is more of the up-close variety—noticeable around the helipad, but less if you’re an observer some distance away. Heavier helicopters tend to be less quiet because of the larger amount of thrust they require—they have more weight to lift, after all.

The degree of sound from the individual sources depends considerably on both the flight condition and where the observer is in relation to the helicopter. When the aircraft is flying at cruise speed and is approaching, a person is likely to hear the main rotor as the helicopter comes towards him. When it is closer, and passing overhead, the tail rotor and engines are predominant. In takeoff and approach, these individual sources of sound can change, due to the machine’s different power and thrust requirements.

And helicopters can be more or less quiet in certain flight conditions, such as during an approach. This is due to blade vortex interaction (BVI), a type of loading noise. Each main rotor blade also produces a strong tip vortex whose trajectory travels downstream from the rotor in an approximately epicyclical manner. In approach and sometimes at moderate speeds in level flight, the vortex trail may intersect the paths of subsequent blades, producing impulsive noise that’s sometimes referred as “blade slap.”

When a helicopter is making an approach, the main rotor blades can move into the path of a vortex produced by the blades ahead, producing a sound called “blade slap.”

Of course, our perception of sound is just as important a factor in judging how quiet, or not, a helicopter is. We tend to be more bothered by impulsive, tonal, high frequency sounds, but the duration of one’s exposure to the sound also matters, irritants that Airbus is addressing with adjustments in landing procedures, for example.

Why sound matters

Fifty years ago, helicopters were louder because sound-generation phenomena were less well understood. Several efforts have been made to reduce helicopter sound since the 1980s, and sound certification limits have been introduced. Such limits tend to be more stringent with time, pushing manufacturers to work on sound reduction technologies. Some types of sound have been dealt with through innovation; new rotor designs that reduce the speed at the blade tip now lower high-speed interaction noise. But sound reduction is also strongly motivated by financial need: helicopter operations and businesses are often restricted by the push towards quiet operations in sensitive areas. Operators may also need to compensate people for sound attenuation on surrounding buildings.

And reducing sound has an impact on the future, if we wish to see one in which helicopters, VTOL* aircraft and drones free up our roads by delivering packages or taxiing commuters.

Innovations for the whole range

Since the development of the Fenestron® tail rotor, which pioneered the first concrete steps toward making an impact on helicopter sound emissions, Airbus has taken sound reduction to heart, over the years introducing sound-reducing technology on its range.

The H135, H145, H175 and H160 all include an automatic variable rotor speed control system that automates the rotor towards lower rotational speeds when the helicopter flies close to the ground. Another example is blade shapes; the H160, newest in the fleet, has innovatively shaped BlueEdge blades which are meant to reduce BVI noise—with very positive results.

The manufacturer’s Bluecopter demonstrator has tested sound reduction technology such as optimised blade and stator designs on the Fenestron, the acoustic liner in the Fenestron’s shroud and the active rudder on the tail fin. Much of this technology is meant to equip the fleet in the coming years.

The future of sound

VTOL aircraft already fly over some of our cities. Helicopters transport medical patients to urban hospitals. Sound is part of the world we inhabit. The next step, says Tomasz Krysinski, Research & Technology Director at Airbus, is the “design for sound” of new aircraft, particularly to address the urban air mobility market.

One focus is exploring new configurations for air vehicles, to leverage on possibilities that could trigger significant benefits in sound reduction. The CityAirbus and Vahana VTOL vehicles with their multiple propellers, now in the demonstrator phase, will need to meet a level of sound acceptance that will be significantly more stringent to operate above cities.

“It’s not only about designing silent products, it’s also about designing silent procedures for our products,” says Krysinski. To this end, the company is also working on another kind of sound reduction: optimising takeoff and landing procedures, and lowering real-life operational sound. BVI occurs in certain glide slope angles and not in others, so by designing a landing procedure with a steeper glide slope, sound can potentially be lowered. This is just one of the solutions being considered. Climbing procedures, too, may come under scrutiny.

“Certification for sound is done under flight conditions that are imposed by authorities,” says Krysinski. “They are not necessarily the procedures flown by our customers daily. We are working on impacting the real sound people hear coming from our products.”

*VTOL: vertical takeoff and landing