Now four years into their successful partnership, the Airbus Foundation and the Connected Conservation Foundation are continuing to support conservation projects around the world by launching the fourth round of the Satellites for Biodiversity Award. As in previous rounds, winners will gain access to cutting edge satellite data, now enhanced by AI-driven insights. One of those previous winners is Chulalongkorn University - Ethiopia, concerned with the protection of the Ethiopian wolf, the most endangered carnivore in Africa.

When one thinks of African geography, the diverse alpine climate of Ethiopia’s Bale Mountains might not be the first image that jumps to mind. With five distinct ecosystems – woodlands, grasslands, meadows, moorlands and forests – the Bale Mountains National Park is home to a variety of rare flora and fauna, from towering giant lobelia to the mountain nyala.

On the Sanetti plateau, the high altitude makes for a mist-shrouded landscape. It is here, on this seemingly barren expanse, that we find the endangered Ethiopian wolf. With its reddish coat and white markings, it looks more like a large fox to the untrained eye. In fact, this is the world’s rarest wild canid.

Approximately 500 of these creatures remain, and around 70% of the extant population is here in this 2,150 km² nature reserve.

Why is the Ethiopian wolf at risk?

This ancient ecosystem has survived the test of time, with the isolated landscape of the plateau remaining relatively untouched by outside influence for millennia. In more recent years, this unique ecosystem was recognised by UNESCO and placed under legal protection. However, these safeguards have been insufficient to halt the pace of change.

Although the Ethiopian wolf population has been declining steadily for decades, this trend has accelerated in recent years. Between 2019 and 2024, there has been a tenfold increase in human settlements inside the park, which has fractured the landscape. This change was mostly driven by the arrival of pastoral communities – displaced as a result of the environmental pressures they themselves face. In the lowland regions where these communities originate, drought and the declining availability of pasture have forced these groups to migrate in search of pasture and food during the dry season in particular. With a 42% increase in the amount of farmland in the park, wildlife corridors have been disrupted, diseases have been introduced by stray domestic dogs and habitats have been altered. As is the case in so many other ecosystems around the world, human activity is having the unintended consequence of upsetting the natural balance in the park.

Pleiades Neo (C) 2024 Distribution Airbus DS

What happens if the wolf disappears?

To appreciate the ripple effect – also known as a trophic cascade – that could unfold if the Ethiopian wolf were to disappear, we need look only to another wolf population on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean: the grey wolf of Yellowstone National Park, in the United States.

In the 1920s, the grey wolf was wiped out. Its numbers dwindled first due to disease, and then due to government eradication programmes. With the apex predator out of the picture, the local elk population exploded. No longer forced to keep moving to avoid wolf attacks, they overgrazed plants and trees like willows and aspens. This led to a decline in beaver populations, who were lacking those plants and trees as an important food source. With fewer beavers, riverbanks changed. Songbird and fish populations suffered. The whole ecosystem was impacted. This transformation demonstrated how the removal of the keystone predator – in this case, the grey wolf – can be disastrous. When wolves were reintroduced in the 1990s, over time, much of the damage to the park was reversed and the landscape mostly recovered.

Turning back to Ethiopia, the Ethiopian wolf also has a vital role to play in maintaining the delicate balance in the afroalpine ecosystem in the Bale Mountains. The wolves regulate the rodent population, mostly eating giant mole rats. This in turn keeps the alpine vegetation in check. If the wolf population were to continue to decline, we could see a similar pattern: the mole rat population would likely surge, overgrazing would impact soil health and reduce the richness of plant species in the area, a concern for other herbivores. Taking out one piece of the chain can have far-reaching consequences.

An additional challenge facing the Ethiopian wolf relates to the spread of disease. As pastoralists have been forced to seek new land, their arrival has altered the landscape. Herders have come to the area, bringing with them domestic dogs, which are often unvaccinated. Despite their common ancestry (albeit some tens of thousands of years ago), interactions between Ethiopian wolves and domestic dogs are often territorial, and these tense interactions can spread diseases such as rabies and canine distemper. If a wolf contracts one of these diseases, their pack can be decimated. The combined impact of habitat loss and disease risk creates a serious and urgent challenge to the long-term survival of the park’s unique biodiversity.

How are local communities helping?

Reconciling the communities that coexist with the Ethiopian wolf is a vital step in promoting coexistence between humans and wildlife. In the park, an ambitious community engagement programme called Peaceful Co-existence has targeted five key villages and involved more than 200 residents. Trainers from the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute (EBI), fluent in the local language Oromiffa, worked with representatives from the Bale Biodiversity Centre, Bale Mountains National Park, and regional authorities to adapt training materials such as posters and visuals to the local context. Community sessions with diverse groups including elders, women, youths and teachers, were able to engage in a two-way discussion with conservationists.

Workshops and education initiatives have helped to build trust and strengthen relationships between community leaders and conservation organisations, as well as improving local understanding about biodiversity, the ecological importance of this unique landscape, current threats facing local wildlife and practical ways to protect the species that call the park home. The local community lives harmoniously alongside the wolves, and engages in voluntary park monitoring activities to evaluate progress.

These local communities have also played a valuable role in deepening the understanding of the park’s evolving ecosystem. They help to validate satellite maps and add much-needed on-the-ground knowledge to the high-tech data needed to inform policy changes and management practices.

How do satellites and AI provide conservation insights?

Conservation efforts in this diverse landscape rely on a deep understanding of what exactly is happening in the park. With elevations ranging from 1,450-4,377 metres above sea level, satellite data is an indispensable resource. In the Bale Mountains National Park, Chulalongkorn University and the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute used high-resolution imagery from Airbus-built Pleiades 1A (55.6 cm resolution) and Pléiades Neo (30 cm resolution) satellites, provided by the Airbus Foundation. In addition, Connected Conservation Foundation provided funding and technical support, helping to unlock key insights from the data.

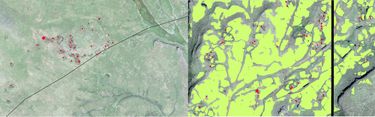

The satellite data revealed increasing settlement clusters close to the boundary of the park. In comparing 2019 to 2024 data, a stark increase in human settlements is clearly visible. In this period, settlements increased from 388 to 3,506 within the park boundary. In the 10km buffer zone that was also monitored, the number of structures grew from 903 to 6,180.

Without the power of an eye in the sky it would not be possible to gain such comprehensive insights into the scale and pace of change.

AI-driven mapping showing increased settlements and farmland within Bale Mountains National Park

How is the Satellites for Biodiversity Award supporting conservation efforts?

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus observed some 2,500 years ago that the only constant in life is change. So, the challenge facing conservationists is to gather the best possible insights as to the pace and scale of change in unique ecosystems like the Bale Mountains National Park. These insights can then inform effective action to protect the species that call the park home and to foster a balanced coexistence with communities in and around the park.

This is why biodiversity projects, like the ones supported by the Satellites for Biodiversity Award are so important. The powerful combination of on-the-ground expertise and data-driven insights gained from satellite data allow conservationists to make better informed decisions.

Applications for the fourth round of the Satellites for Biodiversity Award are now open. Applicants can win access to Pléiades and Pléiades Neo 30-cm resolution satellite imagery, in addition to HD15 enhanced visual renderings.

Produced by applying a proprietary algorithm using AI and machine learning, the HD15 imagery can improve data accuracy by restoring and refining existing features of the Pléiades Neo imagery. For example, a third-round Satellites for Biodiversity Award winner, Victoria University of Wellington, is using HD15 enhanced imagery to detect albatross nesting sites on Campbell Island / Motu Ihupuku (an uninhabited subantarctic island of New Zealand). The team will be testing if AI enhancements can distinguish between active nests and abandoned ones in the satellite imagery, capturing subtle indicators of nest activity.

Submissions for the Satellites for Biodiversity Award are open until 19 December 2025.

Airbus Foundation latest news

Continue Reading

The last stand of the Ethiopian wolf

Web Story

Airbus Foundation

Find out how Airbus satellites and local partnerships are driving conservation

How aviation partnerships are strengthening humanitarian logistics

Web Story

Airbus Foundation

2024: The Airbus Foundation’s year in review

Web Story

Airbus Foundation

Saving the giant pangolins of Nyakweri Forest

Web Story

Airbus Foundation

Airbus Foundation and Solar Impulse Foundation launch call for projects

Web Story

Sustainability