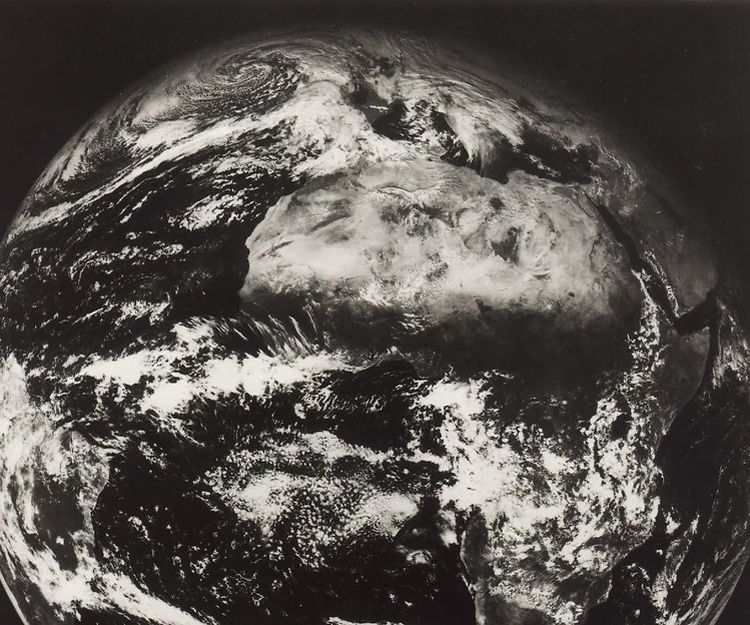

Meteosat-1 was constructed by an industrial consortium, which included what is today Airbus’ Space Systems. Orbiting the earth at 36,000 kilometres, it sent detailed images back to Earth every 30 minutes.

The satellite provided not only information on cloud cover and weather fronts but also infrared imagery showing temperatures and the distribution of water vapour in the atmosphere. Thus, meteorologists were given a global 3D image of the planet’s weather pattern.

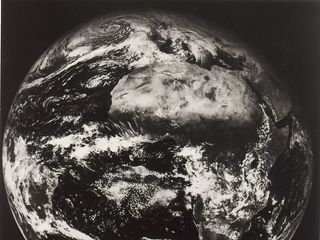

A global overview

Today, seven second-generation Meteosat satellites are in orbit around our planet, relaying images of their part of the world every 15 minutes. These geostationary satellites are responsible for large-scale monitoring of the Earth’s weather patterns. Within their own orbit, they move at the same speed as the Earth, and monitor their individual parts of the planet, with each satellite covering a third of the Earth’s surface. However, they cannot monitor the two polar regions as they are stationed above the equator.

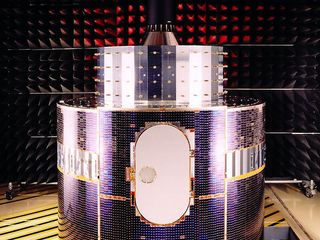

MetOp for close ups

The gap in coverage is filled by polar-orbiting MetOp satellites, which have been aloft since 2006. The two European satellites, MetOp-A and MetOp-B, were developed and produced by Airbus for ESA and the European meteorological organisation, EUMETSAT. They orbit the Earth at an altitude of only 830 km and complete one Earth orbit in some 100 minutes. Because their orbits are 42 times closer to Earth than those of the geostationary satellites, the observation data provided by MetOp satellites is much more detailed. Through the progressive innovation in this field, we are able to be more precise in our weather forecasting, to predict natural disasters better, and to better measure issues like climate change, the progressive melting of polar ice and the rise in sea levels.

Forecast

The third and final first-generation MetOp satellite is expected to be launched in autumn 2018. Main goal for this new MetOp is the data continuity till (at least) the MetOp-second generation will be on duty.