Although it is extremely difficult to predict exactly when a volcanic eruption will occur, it is possible to closely monitor the world's active volcanoes. Warning signs such as increased seismic activity or plumes can easily be observed from the ground, using multiple sensors and cameras, but also from space, thanks to satellites.

Firstly, radar satellites, which can see through clouds, day and night, can measure and map minute changes in altitude on the slopes of volcanoes, as well as in the central part of the crater, thanks to their very high sensitivity (of the order of a few millimetres) - see explanations here. The more active the volcano, the greater the frequency and intensity of these changes.

In addition, optical satellites – ones that take pictures like camera pictures – are ideal for monitoring plumes and lava flows, as well as the formation of new volcanic islands.

Hunga Tonga July 2, 2014

Hunga Tonga January 19, 2015

Hunga Tonga May 12, 2019

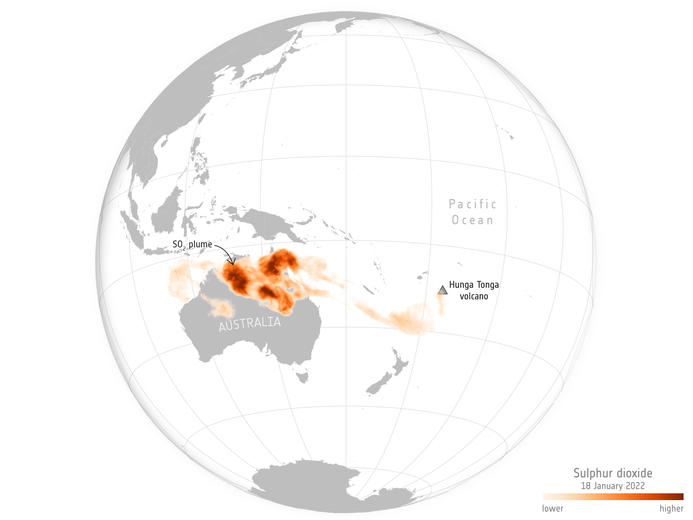

There are also other satellites that are very useful in helping to monitor volcanoes, such as Sentinel-5P, which studies atmospheric pollution, notably by measuring sulphur dioxide levels. This data is very useful after a massive volcanic eruption, as it allows us to estimate the impact that the quantity of gas released may have on the planet and therefore on its inhabitants.

Finally, the satellites measuring winds aloft, such as Aeolus satellite, also provide essential information for studying where and how this cloud will disperse.

The eruption, or rather the explosion, of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano near the Tonga Islands has just demonstrated the usefulness of having access to such satellite resources.

The first images of this eruption that reached us were taken in real time at an altitude of 36,000 km by the meteorological satellites that cover the Pacific region. Space agencies and commercial operators quickly tasked their satellites to assess the extent of the damage to the surrounding inhabited islands and to help prepare the intervention of rescue teams.

The plume created by the explosion initially prevented aircraft from flying, but also prevented optical satellites from providing usable images. But very quickly, and despite the persistence of a significant haze due to the various gases and particles in the air, it was possible to make an initial estimate of the damage, notably with the Pléiades and Pléiades Neo satellites. New images acquired the following days have enabled these estimates to be further refined.

Without waiting for the clouds to dissipate, the Sentinel-1 radar satellite showed that the entire crater had simply evaporated.

The Sentinel-5P satellite is currently following the evolution of the large plume of sulphur dioxide that formed, and which quickly reached Australia.

copyright ESA

Tonga was virtually cut off from the world, with all telephone and internet communications cut off. Only the few telephones with satellite links allowed the inhabitants to contact the emergency services.

In summary, satellites such as the ones named above, designed and built by Airbus – or ones to which we have made a major contribution like the high precision radar instrument of Sentinel-1 – are vital resources in times of crisis. They work rapidly behind the scenes to warn, inform and guide those providing emergency relief.